Do you eat everything you see? In a recent article, Gray Cook makes a comparison between nutrition and exercise, and then highlights the fact that people probably gain most from the Paleo diet (or Banting in South Africa) because it is an elimination diet. These diets don’t necessarily add anything new, as the bulk thereof consist of things many people consume daily. It does however eliminate various things like refined sugars, synthetic foods and grains, which cause ill-health symptoms (allergenic, intolerance or insulin related reactions), and was previously consumed in excess by many.

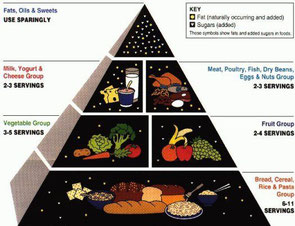

Before we make the connection with exercise, I’d like to add another angle to this comparison: Some years ago, when Tim Noakes and Kie still proposed an ideal diet to consist of 60-70% Carbohydrates, there were no distinctions made between good or bad Carbohydrates. The reason was simple: scientific reduction of food does not and cannot make qualitative distinctions, due to empirical science’s exclusive concern with the quantifiable aspects of macro nutrients. Researchers therefore neglected the possibility that two Carbohydrate foods might have very different effects on the well-being of their consumers, and or effect certain people differently than others.

The critical questions I posed as a student to teachings that sportsmen should Carbo-load on pasta and whole wheat bread, has now become part of the rationale for proposing Low-Carb diets. Thanks to more and more seekers opposing the ‘scientific’ nutritional data with contrary evidence from personal experience, it has become an accepted principle that good health is a cornerstone to sustainable performance. If gluten allergy /intolerance causes an autoimmune response or digestive complications, then most certainly Pasta or common bread should be avoided in favour of better carbohydrates like Sweet Potato.

Any attempt at improving your nutritional intake has to start with the health of your digestive system. No matter how great your diet, if your system is not functioning in balance, foods might not be broken down properly and nutrients not effectively absorbed. This implies that it’s not only what we eat that promotes health, but also when and how. There are times when abstaining from food for a limited period is key to restoring balance. Fasting or intermittent fasting has been a common health practice for centuries in most cultures before this generation…

As one of the many carry-overs to exercise, Gray says that some of us are in need of eliminating those exercises that are not working for us as individuals. An exercise or movement that causes pain or excessive stiffness after a workout (far beyond the normal DOMS), should be a red flag. This is an indication of overuse and compensatory movement, which could eventually lead to the formation of scar-tissue and dysfunctional movement patterns.

Exercise seems to be lagging behind nutrition however, and according to Gray “exercise is always about 15 years behind”. There still remains big ignorance to the fact that not all exercise is suitable for all individuals. Even in ‘functional training’ environments, were bigger movements are chosen in preference to isolated movements, many trainees do not possess the movement competency to perform these ‘functional’ exercises.

The problem is that many come to exercise not understanding that, as with any other skill, we need to respect the developmental process. If your functional movement ability (competence) has been compromised through sedentary living, injury, poor movement habits, or acquired movement dysfunction, whatever the case might be, you’re probably not ready to perform the loaded movements that your finely tuned fitness trainer can.

Notice I didn’t say “not able to” perform. The key concept here is not whether you can do the exercise, but rather how. As with food, the real proof of its benefit to you is not whether you can eat it, but how your body responds to this food. Exercise is not a magic bullet, but rather a stimulus which affects certain responses in the body. To facilitate a positive response, exercise should be a positive learning experience.

Without the necessary mobility and/or stability you might not be able to get into the right position, never mind execute the exercise with control, and gain no motor learning benefit. If you have a poor squat movement pattern and load your squat with weight and/or volume, your brain forgets about moving with integrity and balance, and goes straight into survival mode. We see this daily in gyms around the world: people huffing and puffing while surviving their loads, instead of benefiting from it.

If you don’t have a minimum level of movement competency or integrity, loading exercises that are unsuitable for you with weight or repetition, reinforces the movement dysfunction you already have. Adding strength to your poor squat pattern will make the spasm in your inner thigh harder, or add more stiffness to your thoracic spine. You are adding strength to dysfunction, making it more difficult to correct.

Nature requires a movement foundation of basic function on which specialized skill can be build. For babies to first crawl before they walk is common sense. This natural and common sense approach has been lost in the instant-everything-culture of our time, and most seem to not have the patience for addressing limitations before trying to develop specialized skill.

A big problem in the industry is the lack of measuring basic functionality. To draw a map for any trip, knowing where you want to go is only half of the information needed – of similar importance is knowing your starting point. Eager gym goers are shooting off at full throttle for their destination without knowing the baseline of functional competency they start from. Sadly, the outcome is more than often injury within 3 to 6 months from when they took off.

An even bigger problem underlying the previous one, is the lack of a clear definition of the term functional. This term has been used to suit whatever we are selling, whether functional training, functional exercise or functional rehabilitation, it is implied that what is offered is more efficient, holistic or appropriate. Such ambiguous statements without evidence of measuring methodologies against functional standards, are nothing but hot air.

In an older article Gray brilliantly depicts this scenario of professionals advocating their favourite methodologies without evidence: “It’s like we’re all riding in a car with a broken speedometer, all riders commenting on how fast we’re going — much more opinion than fact. Unless we have a gauge to measure the correctness of our opinions, we should find another way to objectively calculate the speed of the car.”

Function could mean different things to different people. For one it means to tie his own shoelaces, and for another the ability to perform an Olympic Lift. Although we express our functionality in different ways, we all share one fundamental attribute: we are human. Our fundamental movement needs are specie specific, long before they become sport or activity specific. A standard baseline for function should therefore focus on basic movement competence.

This is exactly why the FMS was developed. The Functional Movement Screen objectively measures your ability to perform 7 fundamental movement patterns against minimum standards. The inability to meet any of these standards are significant of a movement dysfunction, and provides information about where exactly a training program should start from. An overall score on the FMS of 14 or below (out of 21), can also be an indicator of higher risk of injury.

Write a comment